A review paper published in Anaesthesia looks at factors associated with mortality in COVID-19 in patients admitted to intensive care (ICU), finding that male sex and increasing body mass index (BMI) are not associated with increased mortality.

Dr Jamie Hartmann-Boyce, Senior Research Fellow, Departmental Lecturer, and Director of the Evidence-Based Health Care DPhil Programme, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, said:

“This new review combines results across 58 studies of over 44,000 people admitted to intensive care units with COVID-19. Like previous studies, it finds that long term conditions, including diabetes and high blood pressure, appear to increase the risk of dying with COVID-19. However, unlike previous studies, the authors state they did not find a clear relationship between male sex and dying with COVID-19, or between body weight, measured using BMI, and dying with COVID-19. Whilst at first glance this may seem surprising, there are a few things to bear in mind.

“Firstly, these studies were conducted only in people admitted to intensive care. Lots of things impact the decision to admit someone to intensive care, and this could be affecting the results. Secondly, in this data set, men were more likely to die with COVID-19, but the increase in risk observed was relatively modest, meaning the authors could not rule out no difference based on sex. Risk also appeared to increase as body weight increased, but again the increase was modest and the authors could not rule out no difference. Finally, there are lots of different ways to look at the question of whether raised BMI increases risk. Here, the authors looked at the impact of increases in BMI units, instead of splitting the data by BMI category – for example, other studies have compared people in the ‘obese’ BMI range with those in the ‘normal’ BMI range. This could have impacted their results. Additionally, the average BMI in this data set was not in the ‘obese’ range, and we don’t know how many people living with obesity were admitted to intensive care in these studies. This could also affect the results.

“Though the findings from this review may help decision-making in intensive care, they should not be interpreted as contradicting results from large studies and other reviews which show that in the entire population (not just those admitted to intensive care), male sex and raised BMI are risk factors for worse outcomes from COVID-19. The best thing people can do to reduce their risk of dying from COVID-19 is to take both vaccine doses when offered.”

Prof Kevin McConway, Emeritus Professor of Applied Statistics, The Open University, said:

“This research puts together information from a large number of different previous studies of factors associated with mortality in people with Covid-19 admitted to intensive care. The previous studies have examined a large range of possible factors that might affect the risk of death in patients with Covid-19 in ICU, and it was already known that the position is complicated, with a large number of potential risk factors that are likely to interact with one another. The statistical analysis in the new research seems to be appropriate and follows the standard guidelines for doing this kind of systematic review of previous work, so it is sound work, but inevitably it has some limitations.

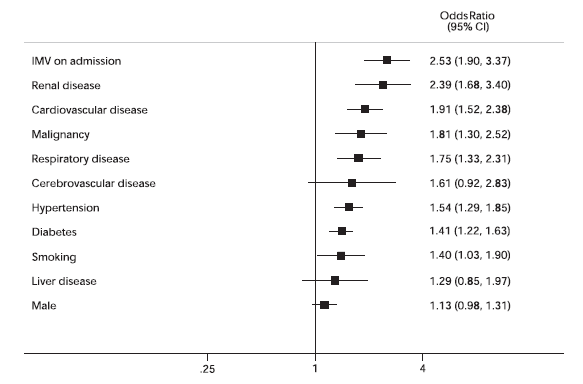

“The researchers conclude that there are associations between several of the factors that they examined and the risk of death, for patients who are in an ICU with Covid-19. It’s important to be clear what they are looking at here – it is the risk of death in patients who have been admitted to ICU. It is not (for instance) the risk of being admitted to ICU and then dying, in patients who are ill with Covid-19, or in patients who have been admitted to hospital (but not necessarily ICU). The risk factors found in this research are generally the kind of factors that are already known about – higher risk of death in older people, in smokers, in people with various pre-existing health conditions, and in patients with various measures of inflammation and of disease severity. Despite these generally being known risk factors, the new study confirms that they are indeed risk factors, and gives measures of the difference in risk associated with each of them, averaged across all the studies that were reviewed. That’s all useful.

“However, the new research did not confirm that being male, or having a high BMI, were associated with a higher risk of death, for patients in ICU with Covid-19. It’s not very clear (to me at least) how much evidence there actually was from previous studies that being male is associated with higher risk of death, for patients in ICU. The paper on the new study quotes three other references on this. One of them did indeed look for an association between the patient’s sex and death risk, for patients already in ICU, and it found no association. The other two appear mainly to have looked at the risk of death across hospitalised patients who were not necessarily in ICU already. They did find that men had a higher risk of death. But that doesn’t tell us directly whether men are more likely than women to die, given that they have been admitted to an ICU, or that men in hospital are more likely to go into an ICU but, once they are there, they don’t have a different risk of dying than women who are in ICU. (And there are other possibilities.) If it is indeed the case that men in hospital are more likely than women to go into ICU, but that, once there, the sexes don’t have different chances of dying, that would broadly be in accord with what this new study reports, because it is looking only at the second part of this sequence of events – at what happens after people are in ICU. The new research did not look at the risk of ICU admission, for people in hospital. It does, however, report that almost 70% of the ICU patients in the studies that it reviewed were male, which might be because being male is associated with a higher chance of going into ICU once one is in hospital. This is beginning to sound like nit-picking – but it does illustrate that different questions can have different answers, and understanding what is being investigated is important. The position with BMI does seem to be complicated, with some previous studies listing it as a risk factor, others not.

“The wording of conclusions can be important too. The new research reports that being male (and having higher BMI) were not found to be associated with a higher risk of death. But, actually, their central estimate is that the chance of dying for a male in ICU is about 8% higher than for a female. Why they say there isn’t a higher risk of death for males is that there is some statistical uncertainty about that increased risk. It’s possible that the risk in males is anything between about 17% higher than for females, and about 1% lower than for females. Both of these extremes are (just) also consistent with the data. Because it remains possible that the risk isn’t higher for males, the researchers report that there’s no an association. But there could still be an association, that the study wasn’t able to detect with enough certainty, and if there is, it appears more likely to be in the direction of an increased risk for men than an increased risk for women. The position on BMI is clearer – really there’s almost no evidence in this study of an association between BMI and risk of death in either direction.

“It’s important to understand that this research can’t provide definite proof that the risk factors that were found are actually the cause of the differences in death risk with which they are associated. The studies that were pooled for the research were all observational, and in an observational study, any observed associations might be caused by the risk factor, or they might be caused by something else that happens to be associated with the risk factor. So if you pool a lot of studies that don’t provide clear evidence of what causes what, the resulting conclusions also can’t be certain about the cause. That said, the researchers on the new study do discuss possible ways in which some of the factors that they consider could in fact cause a greater risk of death. It does seem quite likely that at least some of them really are involved in causing death to be more likely – we just can’t be sure on the basis of these results.

“It’s also important to understand that the different risk factors were not all measured in every study that was considered, that different studies made different statistical adjustments to allow for associations between risk factors and possible associations with other factors, and that in any case the studies were carried out in different populations and different settings and with (in some cases) different definitions of risk factors or ways of measuring them. (That diversity of studies shows up in the new report finding moderate to high heterogeneity measures across all the factors it considered.) This inevitably means that this new research can’t really clarify how the different risk factors might interact with one another, and that its measures of the increases in risk associated with the factors that it considered are averages across a range of different settings, and might well not apply in some different setting. Overall, this means that the new research certainly can’t tell us everything relevant, but it can and does tell us quite a lot of useful information.”

Prof Steve Goodacre, Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Sheffield, said:

“This study looks at highly selected groups of critically ill patients who were admitted to intensive care. It therefore provides very useful information for intensive care specialists but should not be used to draw conclusions about the wider population with COVID-19. Male sex and increased BMI increase the risk of severe illness, so you are more likely to need intensive care admission if you have COVID-19 and are male or have increased BMI. The study shows that once people have become critically ill and have required intensive care admission, male sex and increased BMI are not associated with an increased risk of death.”

Dr Stephen Burgess, Programme Leader at the MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge, said:

“This is a classic example of selection bias – it could come straight out of a textbook. The investigation only considers those who were admitted to ICU. So those who were not sick enough to be admitted to ICU were not part of the investigation – as these individuals weren’t included in the analysis, the associations between variables in the selected sample become meaningless.

“As a simple illustration, let’s imagine that there are two categories of people: underweight and overweight. For a given severity of COVID, if overweight people are more likely to be admitted to ICU, then there will be more overweight people with mild COVID in ICU. Whereas proportionally more underweight individuals in ICU will have severe COVID. Hence by ignoring those who weren’t admitted to ICU, your comparison is not a fair one – you are comparing underweight individuals with a more severe distribution of COVID severity with overweight individuals with a less severe distribution. It’s no surprise that the overweight individuals tend to do better (or at least, no worse).”

Dr Baptiste Leurent, Assistant Professor in Medical Statistics, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said:

“It is probably an overstatement to conclude that BMI and sex are not associated.

It would have been more appropriate to say something like “less associated than other risk factors”, or “did not find evidence of an association”.

“If you look at the forest plot below, you can see that the association with gender is around 1.13 (95%CI: 0.98-1.31), so the male may have around 13% higher odds of dying, which I agree is not much, but not 0 either.”

‘Factors associated with mortality in patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care: a systematic review and meta-analysis’ by E. H. Taylor et al. was published in Anaesthesia at 23:01 UK time on Tuesday 29 June 2021.

DOI: 10.1111/anae.15532

All our previous output on this subject can be seen at this weblink:

www.sciencemediacentre.org/tag/covid-19

Declared interests

Prof Kevin McConway: “I am a Trustee of the SMC and a member of its Advisory Committee. I am also a member of the Public Data Advisory Group, which provides expert advice to the Cabinet Office on aspects of public understanding of data during the pandemic. My quote above is in my capacity as an independent professional statistician.”

None others received.